- Home

- Luke Horton

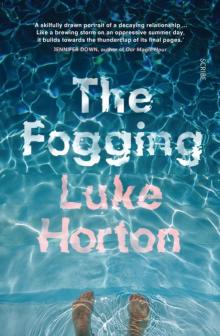

The Fogging

The Fogging Read online

Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Acknowledgements

The Fogging

Luke Horton’s writing has appeared in various publications, including The Guardian, The Saturday Paper, and The Australian, and was shortlisted for the Viva La Novella prize. The former editor of The Lifted Brow Review of Books, he currently teaches creative writing at RMIT, and is a member of acclaimed indie-rock band Love of Diagrams. The Fogging is his debut novel, and was highly commended for the Victorian Premier’s Award for an Unpublished Manuscript in 2019.

Scribe Publications

18–20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409, USA

First published by Scribe 2020

Copyright © Luke Horton 2020

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

9781925849592 (Australian edition)

9781925938524 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

For Mum, Dad, Jess, Antonia, and Albertine

1

They took the evening flight, so the plane was full of people trying to party the six hours over. Whole rows of early-twenty-somethings ordering drink after drink, sharing their iPhones and earbuds around, and laughing uproariously. When Tom turned to place them, their flushed faces were green in the reflection of their screens. Either that or it was young families watching movies — groups of one kind or another.

In the row ahead there were three young men, each six-foot-something, dressed smartly in button-down shirts and chinos, with combed-back hair flopping forward, square jaws, and squared-off hairlines across broad necks. They looked like ex-high-school football stars on a night out, or like mannequins that had come to life. They drank cans of beer and Bourbon and Cokes, and flirted shamelessly with the female flight attendants, who, by and large, appeared receptive to it. Every now and then, one of the young men would lean in to whisper something in his friend’s ear, and they would convulse with silent laughter, the whole row of seats shaking under them. They were oddly intimate with one another, Tom thought: forever touching and cradling and even kissing each other’s heads as they laughed. He craned to see them communicating with other passengers via the seat-to-seat chat on their screens, but couldn’t make anything out. They seemed to be egging each other on, pushing each other to be bolder, ever more risqué in their exchanges. Then they would shake their heads and convulse with laughter again, with their fingers pressed into their eyelids, at either the things they said or the things being said in return.

By the time the turbulence hit, though, all three of the young men were asleep, and the cabin had fallen quiet. And Tom had become complacent. He’d had two beers and two Valium and had finally fully relaxed. Directly after the Valium and the beers, which he’d ordered in quick succession and drunk as fast as he could, he’d felt better than relaxed, he felt transcendent. Just for a short while, as the alcohol interacted with the pills. A woolly, dull kind of grace, settling thickly over his ringing nerves. He’d looked over at Clara, who was asleep, and he’d swelled with feeling: he loved and was loved. Everything in the cabin was immaculate and vivid: the soft curve of Clara’s upturned cheek, rising and falling minutely as she slept; the breathing bodies all around him, shifting their weight in the low light; the pale, finely textured moulded plastic of the seat backs. Soon, of course, he dropped down from these heights, plateaued, and, eventually, found he was close to sleep himself. Then, with the first yank off course, he was wide awake again.

His legs went first. They began to spasm, strangely — violently. This was new. Then came the sweat. The inevitable sweat.

Through the turbulence, Tom tried meditation. He tried deep breathing exercises. He settled on the kind of combo of the two that he often fell into — a bastardised technique that he had worked up over the years, and which probably did neither of them justice. It involved repeating the mantra he had been taught while holding his breath for as long as he could, letting it out as slowly as possible, and then holding it out for as long as possible before taking another breath — sometimes swapping out the mantra for counting down from ten instead. It produced a pleasurable physical sensation, as his stomach contracted and his fingertips and legs tingled, became weightless, and lifted off from the rest of his body. When this happened, he would try to picture the anxiety, the excess energy, running out along his limbs and exiting through his extremities. But none of it ever really worked. Right now, it had calmed him a little, perhaps — his grip on the armrests felt less violent — but it wasn’t stopping the spasming, the sweating. Nor was it blocking out intrusive thoughts, wasn’t distracting him from what was happening to the plane, or to his body. Not for more than a second or two. So he also tried holding on to certain images or scenes.

One of these images, which, each time he managed to grasp it, he tried to detail more finely as a way of holding on to it longer, was of Clara earlier that day. She had been wearing a dress with a print of large blue flowers against a faintly yellowed white. He hadn’t seen her in that dress for a long time — several years, at a guess. It looked good on her, but it was the way she’d moved in it, the way she’d appeared at the door when he got home, excited, and disappeared back into the house, moving swiftly through the rooms, still packing, that made him think of it. How different she’d seemed.

As in real life, the Clara in his head had a few cotton threads hanging down the short sleeves of the dress onto her arms. She had cut the sleeves back when she got it and never bothered to hem them. He focused on these. How many, how long, the freckles on the pale arms beneath. They were in the kitchen. He curled his fingers around the threads, tore them off, one by one, as he had wanted to do ever since she’d cut them. Sometimes at this point in the fantasy — he lost it, it floated back up — her dress would slip off, too, somehow, and she stood naked before him. He could not picture her well like this. Then they had sex, on one of the kitchen chairs, like they had never done in real life. He could not picture her well like this, either. He couldn’t picture either of them well like this. He had to redo the scene several times to get it right: how it might actually work, technically, without the usual embarrassments, and in any other scenario than in their bed, or, perhaps once a year, on the couch. But against the fear, against the sudden jolts and drops, against his legs shaking uncontrollably, convulsing really, trying to helped.

When he wasn’t able to hold on to images or scenes such as these, he squinted. This was better, he found, than completely closing his eyes, where, in the darkness, things too easily catastrophised — the lurching, the overcorrections — and also better than having them fully open, where he could see what was happening to the plane, their once wonderfully stable, sturdy-seeming plane that had run fixedly th

rough the air, like a train along invisible tracks towards Denpasar. Squinting, there were things he could focus on without seeing too much: the upholstery of the seat in front of him; the screen, now blank, mounted upon it; the tray table stowed beneath that. Through the curtain of his eyelashes, all this swam in filmy, vertical lines.

In contrast — he could just make out — Clara’s face was frozen in an expression of delight. Her face was turned to his, but she was looking out from the corner of her eye down the aisle, towards the front of the plane, as if she had woken and turned to say something to him, found him asleep, and her thoughts had drifted — or perhaps she had become distracted mid-thought by the escalating turbulence. Clara had always loved turbulence. It was a strange thing to say about her — because these days she manifested it in no other part of her life, as far as he could tell — but she had a daredevil streak. Turbulence brought it out. It was the same side of her that had thrilled to rides at theme parks when she was a kid on the Gold Coast. She had gone on one ride during their time together (that he could remember) — the Big Dipper at Luna Park — and, coming off the ride, her face was changed, her eyes dilated, like he was sure, if he could see them properly, they would be now.

He had forgotten this about her, like he had forgotten quite how much she loved to travel until he’d got home that afternoon. Up until then, the trip had hovered over them like some awful thing neither of them could quite face, rather than something they were looking forward to — which it had been for a few days when they booked it. After those first days, whenever they did talk about it, they weren’t sure they should even go. They certainly had no money for it. But Tom’s mother had had Frequent Flyer points up for grabs — and one of his half-sisters did, too, it turned out in the end. She had three kids now and wasn’t going anywhere soon. So they’d had easily enough points for return flights, and then the money began to feel almost like an excuse not to go. It just doesn’t seem like the right time to be taking a holiday, Clara had said. He’d said, It never seems like the right time.

But when he came through the door that afternoon, and she’d disappeared back through the house, she was clearly excited. She was talking fast. She told him everything she had packed so far, everything she’d organised, how the key was under the pot in case Lena wanted anything in the house while they were gone, and how Helen was watering the garden for them. Helen had seemed frailer, she’d said, pausing for a moment. They should do something for her when they got back: bake her something, do some work around her house, yard.

Helen was their one friend on the street. They’d met her when she had mulch she was giving away and they came up the street with a plastic tub each, and she was out the front, wanting to talk. They’d never had a friendly neighbour before and didn’t quite know how it worked. The tubs had been filled with old drafts of their theses. One tub each, filled with hundreds of pages, which they’d emptied into the recycling bin on their way out. Now, let’s fill these with something useful, Clara had said.

After finishing the packing — Tom took about five minutes, wedging into one corner of the suitcase an armful of clothes — Clara took the dress back off, said she was just seeing if she might want to wear it over there. Tom said she looked nice in it. She’d probably end up wearing shorts and T-shirts the whole time like him, she’d said, rolling the dress up into a ball in her hands.

Clara loved everything about flying. Airports, crews, fellow passengers. These things occupied her, exercised her to a degree that was always surprising to Tom. She was like that when they first went travelling, all those years ago, when they went off for ten months and spent so much time in international airports: Singapore, de Gaulle, Frankfurt. They hadn’t exactly been frequent flyers since then — there were trips to her parents’ place on the Gold Coast, and two weeks in New York once, for her research and to see some friends — but she was always the same. So quietly content, observing it all. It was dumbfounding to Tom, whose nervousness spoiled any pleasure he might have otherwise derived from it, but he admired it about her. Sometimes he thought he loved her more in these public moments than at any other time. He loved seeing her through the eyes of others — her self-possession, her manners — but also the world through her eyes, seeing what she looked for. In the airport it was moments of awkwardness in the system, mostly, or moments of communion. The confusion at check-in kiosks and bag drops, the immediate rapport between strangers. The quiet, shared humiliations of the security check. And then, on the plane, the infantilising condescension of flight attendants, and the response by passengers to this — all the minute, touching gestures of resistance and acquiescence. They didn’t discuss it much. They didn’t need to: he saw it in her face. They had read the same books. Just this week — he for a class he was teaching next semester, she for a paper she was giving in August — they’d both been re-reading their copies of The Poetics of Space. Dipping back into them, at least.

Meanwhile, the panic was chewing his insides, but it was not escalating. It had maybe even tapered off a little. It had something to do with the turbulence, how consistent it was now, the firming sense it probably wasn’t going to get any worse than this, the sudden jolts, the listing. His legs were spasming still, his thighs mainly — outwards and then in again. But the sweat had not become a flood; he was merely sodden in the usual places. And he was still shimmering, pulsing so hard he imagined it would have to have been visible to others if the cabin lights weren’t dimmed: the panicked blood swelling his veins. But it was dark. No one could see the shimmering. No one could see anything. Not even Clara, who was so close to him. Maybe that was helping, too.

The turbulence subsided, but it wasn’t until they broke through the clouds and he could see the lights of Denpasar that he properly relaxed. He was flooded with endorphins. He was drunk with relief. He drummed on his knees and stretched out his legs and slid down his seat, and he looked over at a sleepy-looking Clara, who was staring into space. And, perhaps for the first time, he was truly excited about the holiday.

Inside the airport, they made their way through long halls and vast carpeted rooms that were more like the floors of an empty office building than an airport. A golden Buddha in one corner and a canang sari every once in a while — one on a windowsill, one on the floor — were the only signs of the country outside.

On the other side of customs, they were met by a teeming crowd of men pressed against a barrier, jostling for position. They walked up and down the line, looking for their names on the boards the men held above their heads. They found their names, or his — they had mistaken Clara for his wife — and the shuttlebus driver, a short, smiling man, jumped up and down to clear the heads and shoulders of those in front of him and point the direction out.

They emerged from a tunnel into the heat. The unbelievable heat. Even at eleven, twelve, whatever it was in local time. It was so hot Tom wondered how anyone could stay out in it for more than a moment, and yet here were dozens of people moving through it calmly, or just standing around in it in groups. His eyeballs stung; his nose burned when he breathed. Fleetingly, for an instant, the press of it, the lack of oxygen, gave him that pause, that sudden falling sensation — like a sudden drop in air pressure — that always preceded a panic attack, but did not itself always become one. Panic’s presentiment. But he didn’t panic; he turned to Clara. She was beaming at him. He found himself beaming back.

The driver had brought his son with him, or his nephew maybe — to show him the business, he said. Although the son was silent, the driver was upbeat and charming, but his English wasn’t good, and they quickly ran out of things to say. Tom and Clara’s lack in this area became palpable, and Tom was reminded of how bad they were at this kind of thing. No doubt other tourists made up for the limited shared language with all kinds of banter, but neither of them was a voluble person, and especially not with strangers. Being here had loosened them up, he could feel that, they were excited, and they were doing their best to

show it, to be responsive — expansive, even — asking the driver questions about his life and his work, about his son, but they kept coming up against the language barrier, and soon the shuttle fell silent. Tom concentrated on the passing scenery, which was by turns grim and exotic, familiar and strange, derelict and bustling: crowded city streets; lamp-lit night markets; flashing billboards that were much like theirs; and the concrete foundations and hanging wires of buildings going up on rubbish-strewn blocks. And everywhere, scooters whipping by with multiple people on them — couples out on dates, children out late clinging to the waists of mothers, one with a woman and a child behind a man driving. Then one with a dog.

Near the hotel, the driver had another go and came quickly to the point. What will do you while you’re here? he asked, finding their faces in the mirror.

As little as possible, said Tom, jokingly, looking at Clara. She looked back. Oh, he tried again, nothing much. We’ll probably just stay on the beach or by the pool most of the time, I guess.

Tom knew this was not what the driver wanted to hear, so he explained that they were only in Sanur for a week or so, and Ubud for a few days after that, and that they were very busy at home and wanted to spend as much time relaxing as they could.

Yes, yes, said the driver, but maybe … Maybe later you want to see the temple, go shopping, go to Seminyak?

Maybe, said Tom, and when they arrived, the driver gave Clara his card. She was saying to the man, Oh wow, that sounds great, thank you so much, and then the man drove away, and Tom, gathering the bags, heard her gasp. He turned to see why. It was clear enough. They had arrived in paradise.

From its profile on TripAdvisor and Booking.com, the place had looked impossibly beautiful, with implausibly charming pools and gazebos and grottoes and ponds and traditional thatched-roof bungalows rendered in Mediterranean colours, amid tropical gardens that wound through the grounds and out to cabanas on the beach. It was the perfect mix of old-world charm and modern comfort — the shots of inside the bungalows showed crisp white sheets and traditional-patterned bedspreads piled high with pillows and littered with pink petals under canopy frames and mosquito nets, pebble-encrusted bathrooms and terraces decorated with wooden statues, and antique writing tables under the honeyed, prismatic light of bamboo lamps. That light alone. Under that light, Tom thought, I would have to be changed. They read every review to check there wasn’t something the photos didn’t show, some hidden flaw, but nothing of consequence came up — maybe a couple of them said it wasn’t quite what it used to be — and now here it was, in the flesh, looking every bit as good as in the photographs, if not better. For here you could feel the heat and hear the sea and smell the fragrant air.

The Fogging

The Fogging